NanoRIMS: A Nanoparticle Reactor Instrumentation and Measurement System

Background

McMaster Engineering Highlight Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OhaVQgD_pT0

What started as an ambitious final year project with three of my closest friends, NanoRIMS took on a life of its own pretty quickly. I would be lying if I said we knew what we were getting ourselves into from the start. Truthfully, this project was really hard. At times, we had no idea if we were going to be able to finish it, or have it work for that matter. At the end of it all, we all learned a lot about Engineering, Intellectual Property, and ourselves.

NanoRIMS, standing for a Nanoparticle Reactor Instrumentation and Measurement System, was to fill a niche within the biomedical sensor fabrication process. Biomedical research in particular has discovered a wide range of applications for gold nanoparticles, ranging from photodynamic therapy for treating skin diseases, photothermal therapy for cancer treatment, X-ray imaging, drug delivery systems, and biological/chemical sensing. Biomedical researchers are always seeking ways to optimize existing methods and develop novel applications for these useful particles. As a result, there needs to be a reliable and efficient method for synthesizing gold nanoparticles in small batches in order for research groups to be able to study their properties in a controlled setting. At the inception of NanoRIMS, small batch synthesis methods require human supervision and are labor intensive and error-prone. Therefore, the purpose of NanoRIMS was to automate the synthesis and optical characterization of gold nanoparticles in the pursuit of reliability and consistency within biomedical sensing research.

At the end of it all, NanoRIMS had won 1st Place, McMaster Big Ideas Pitch ($400), 2nd Place, McMaster Engineering Competition: Innovative Design, and 1st Place, Early Ideas Winner in the Forge Student Startup Competition ($8000). The latter award provided my team and I to pursue the project at McMaster’s startup incubator during the summer of 2019. It was here where we focused our energy in deciding if NanoRIMS was a worthwhile business to invent our future time and money into. Long story short, we decided to dissolve the company at the end of the summer after looking into the financial horizon and impact of the product in our small market.

It was fun while it lasted and I grew tremendously as a person because of it. At times, I hated the project. Others, it’s all I wanted to work on. And I think that’s normal. I’m thankful for my friends and the support from the Department of Engineering Physics for getting us as far as we did. Sometimes things don’t work out, and that’s okay!

Technical Aspects

NanoRIMS had many technical components that needed a well-rounded team, which included Thermal Management and Control (Heating and Cooling), Fluid Pumping, Free-Space Optics, Image Processing, and a Human-Computer Interface. For brevity, I will only (briefly) discuss the main sub-modules what I focused on.

Free-Space Optics

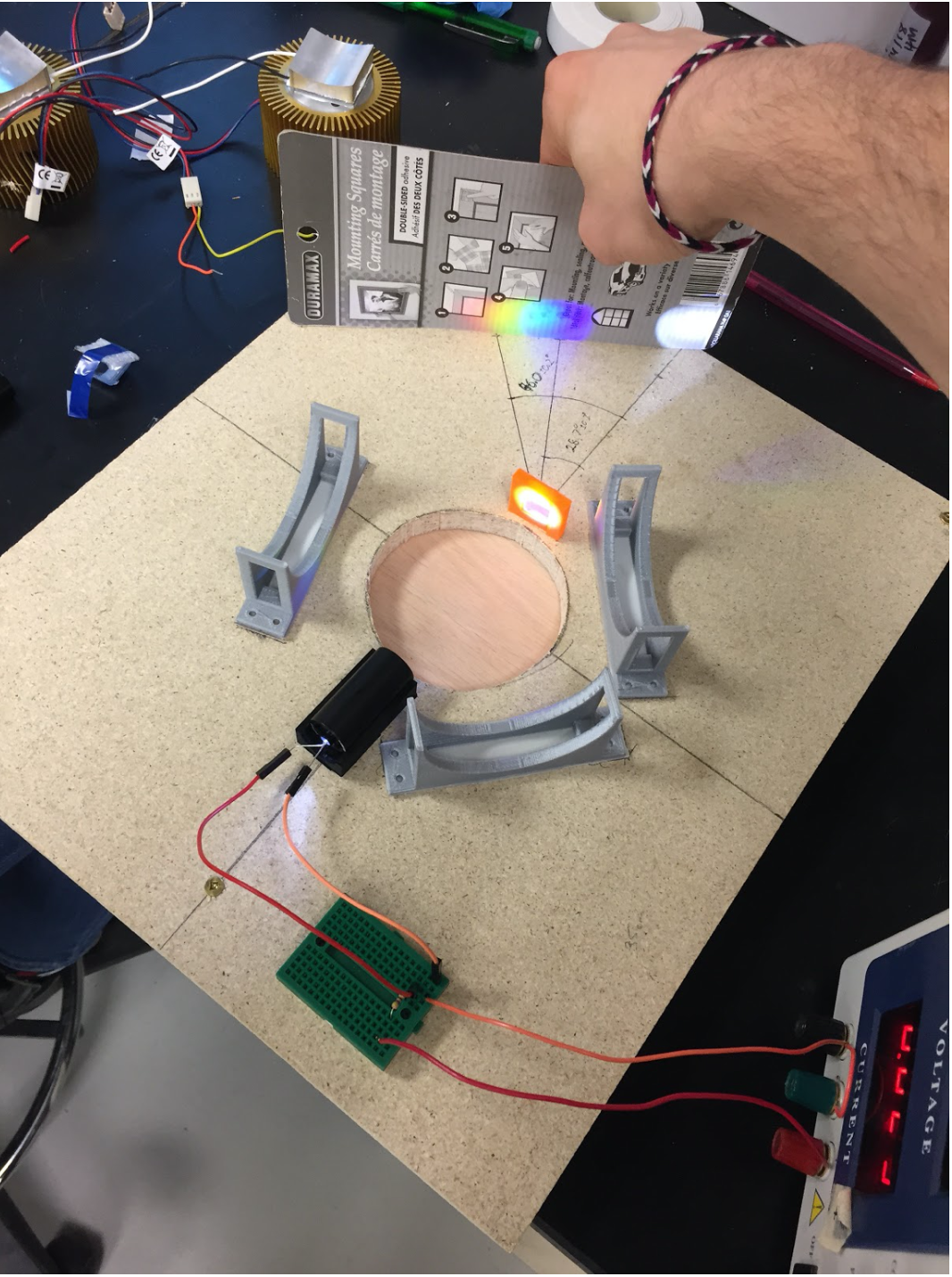

The optical characterization of the synthesized gold nanoparticles used the specific absorption spectra of nanoparticles to identify their size. The relationship between the size of the nanoparticle and the characterisic wavelength of absorption (related to the plasma frequency of the nanoparticle) is suprisingly linear! I designed a free-space spectrophotometer to determine the aborption sepectrum of the nanoparticle solution. This was done using a linear CCD sensor, a transmissive bragg diffraction grating, and a collimated white LED source.

This is a very early prototype of the design. It did not look like this in the final implementation!

This is a very early prototype of the design. It did not look like this in the final implementation!

Image Processing

The initial pumping of the gold solution used for the chemical processes is by far the most sensitive step due to the small amount of liquid that must be added into the mixing volume (~microlitres of fluid). While we were able to pump this small amount using a peristaltic pump, we were not able to do this reliably based on servo-motor steps alone. Further, measuring any weight change in a beaker volume from these drops would be impossible with the traditional load sensor we decided to use. Therefore, an image processing routine was employed to approximate the volume of each pumped drop. We approximate the volume of the drop by imaging the 2D cross-section of the drop right before it accelerates toward the beaker and assuming rotational symmetry. This actually worked pretty well (within a few percent of the true volume). The method was “published” in the McMaster Journal of Engineering Physics: https://journals.mcmaster.ca/mjep/article/view/1964.